Limiters, Compressors, and how to play music loud

The excessive volume of commercials has struck

everyone who’s watched television.

You’re watching a show at a comfortable volume, and there’s a commercial

break, and suddenly you are blasted out of your seat. If you had the volume on 5 it feels like it

just went up to 100, all by itself. How

does that happen?

I was reminded of that question when reading a

new book - Damon Krukowski’s The New

Analog – Listening and Reconnecting in a Digital World. The book tackles that question in the context

of the transition from analog to digital audio and television. Younger readers may not remember that

transition (it was a process, not a single event) but all of us who were adults

in the 1980s lived through it not once but many times.

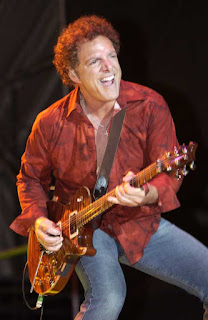

|

| Journey in concert (c) John E Robison |

First there was the transition from vinyl

records (analog) to compact discs (digital.)

Then the audio processing went digital, with smartphone apps replacing

sound processors and digital Bluetooth links replacing analog headphone cords. Call phones started as analog and now are

all digital, and far more capable for the change.

But interestingly, it’s not digital technology

that allows those commercials to blast us.

That is an old analog trick that came from the radio broadcast world

seventy-plus years ago.

In his book Krukowski shows waveform samples

from two versions of a popular song, showing how one version has “normal”

dynamic range and the “loud” version has everything pressed to the maximum. Any listener would say the second version is

louder than the first, but an engineer would point out that the peak energy in

both programs is the same.

Krukowski explains that everything was turned

up, but maximum volume remained the same, so that the soft passages got louder

and the loud passages all became 100%, or full volume. What he does not explain is how that happened

without the music getting horribly distorted.

Building upon his excellent book I’d like to

offer that missing explanation. The answer to how music got louder is

compression and limiting, two technologies that existed for a long time but

which were enhanced dramatically in the 1970s.

I designed compression and limiting systems when

I worked as an audio engineer. Limiters

were originally developed for radio broadcasting, where too much program volume

corrupted the radio transmission.

Limiters prevented that by turning the program down automatically if the

radio announcer got too exuberant.

Limiters operate by measuring the peak level of

a program and turning down volume when a preset threshold is exceeded. If the limiting threshold is set below the

level a sound system can deliver cleanly, the system will in principle always

be clean.

As concert sound systems grew larger in the

1970s sound engineers realized something else.

When amplifiers are driven beyond full power the output waveform is

“clipped” at the maximum level the system can deliver. Clipping turns a smooth musical wave into a

harsh square wave. Listeners know this

clipping as “fuzz,” a sound effect that remains popular today. When one instrument is clipped the effect

sounds purposeful. When the whole musical

program is clipped, the whole program sounds bad.

Sound quality is not the only casualty when

amplifiers clip. Clipping is also

destructive to speakers. In fact, most concert speaker failures are traceable

to excessive clipping. Horn drivers are

prone to shatter and voice coils in speakers overheat and deform.

In 1978 I spent the whole of April Wine’s FirstGlance tour replacing speaker diaphragms after they shattered from the lack of

limiters in Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row rental sound system. It was that tour that showed us the need for

limiters on each of the amplifier banks in a multi-way system.

|

| April Wine - First Glance tour plans photo (c) John E Robison |

Limiters prevent that by keeping amplifiers

from breaking into their clip or overload region. When a limiter is triggering occasionally

it’s said to be “peak limiting” which is an acoustically transparent

thing. The only thing listeners notice

is the absence of clip distortion.

If the program level is raised as the limit

threshold is lowered the limiter begins operating all the time, as opposed to

only during loud passages. When a

limiter is used in that way it’s called a compressor because it’s reducing the

dynamic range (ratio of loud to soft parts) of the program.

Limiters are usually set up with “hard” limits,

meaning material that exceeds their limit threshold are reduced in overall

volume to stay under the threshold level.

Compressors, on the other hand, have “soft”

limits, meaning signals that exceed the threshold are limited, but in

ratio. So a burst that exceeds the limit

threshold by 50% might be limited to just 25% increase at the output.

Soft limits reduce dynamic range without

limiting peak volume so they still allow amplifiers to go into clip distortion (and

radio stations to overload.) Consequently they are not seen in those

applications. Hard limiting is the rule

there. Soft limiting is used when

producers want to compress the dynamic range of a music program; for example to

make it more audible in a crowded area, or to make it seem louder at a given volume

setting.

Soft limiting for compression followed by hard

limiting for overload protection is the technique that delivers maximum average

sound levels in live performance and the loudest program on playback.

Lower frequencies (bass) use most of the power

in a concert sound system so the bass speakers are usually driven by separate

amplifiers. For maximum volume we

applied separate limiters to the bass amps and the higher frequency amps. As

volume rose, the bass would be heavily limited even as the highs remained

untouched, with their full dynamic range.

That bass limiting made for a very solid steady foundation that became

part of the characteristic sound of the disco/soul/funk era.

While some musicians used limiting or

compression as an effect on individual instruments it was mostly a tool to get

more reliability and volume from house sound systems. As far as I know that remains true today.

The main difference between limiters and

compressors of the 1970s and the units in use today is that the sound signals

are now digital, and compression/limiting is done in software rather than by

purpose-built circuits.

Digital limiting allows for a range of

options that could not be accomplished with analog circuits, particularly in

the studio. For example, digital compression software can evaluate a whole song

and apply smoother compression and limiting by looking ahead and behind the

peaks before calculating adjustments.

The main tradeoff of digital limiting is that

it takes time to do the calculations, and the application of limiting

contributes a few milliseconds of delay to the signal flow. Some musicians are bothered by that latency

if they hear the house sound system on stage.

Others won’t notice, or will ignore it as they ignore natural hall echoes

and delays. Analog limiters don't have

delays.

When you hear music or commercials that are far louder than you expect on the radio or tv, you can thank limiting and compression for it. When you hear LOUD on a concert stage, it's limiting, compression, and possibly just a shitload of horsepower in the amplifiers.

John Elder Robison

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

.jpeg)

Comments